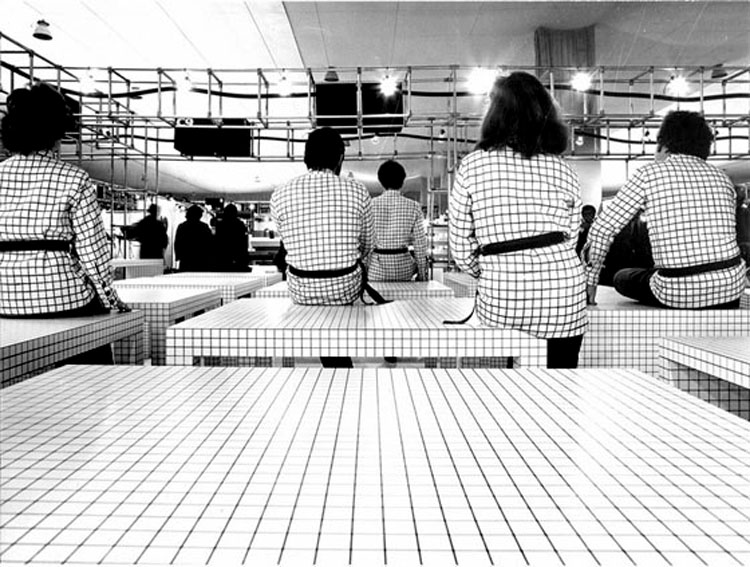

LA GRILLE

Félix Guattari & Diane Arbus

A la clinique de La Borde, en Lozère, Félix Guatari associé au directeur le Docteur Jean Oury, mettent en place un système de responsabilisation des malades et du personnel à travers une grille. Chacun d’entre eux, assignés normalement à un rôle particulier, est contraint de s’investir dans des tâches qui lui sont étrangères. Ainsi que ce soit les medecins, les infirmiers, les employés de ménages, les cuisiniers, les malades.. Ils se voient impliqués (à des degrés de responsabilités différent ) dans la vie de la clinique, et cela à toute heure.

Cadrer le dérèglement

En ce qui me concerne, Je me suis totalement investi dans cette expérience à partir de 1955 ; bien que j’ y aie participé de façon assez suivie dès la phase préparatoire de Saumery. Et c’est durant cette période-là que se sont posés les grands problèmes qui devaient marquer l’évolution ultérieure. Assez rapidement, la clinique a augmenté sa capacité ; elle est passée à soixante malades, puis quelques années plus tard à sa capacité actuelle. Corrélativement, le personnel a augmenté et les anciennes méthodes d’organisation consensuelle, fusionnelle, ne pouvaient évidemment plus fonctionner de la même façon. Quand je suis arrivé, j’ai commencé à m’occuper des activités d’animation et des ateliers. J’ai contribué à la mise en place de pas mal des institutions qui devaient se maintenir de façon durable—quoique toujours en évolution. Mais, assez rapidement, j’ai été amené à m’occuper des problèmes de gestion. Durant les années antérieures, s’étaient instituées des différences de salaires assez marquées, pour des raisons, d’ailleurs, plutôt contingentes, en raison d’arrangements qui se faisaient au fur et à mesure de l’arrivée des nouveaux membres du personnel. Tout ça pour dire qu’il y avait une situation assez floue, assez peu maîtrisée. Une des premières difficultés à laquelle je me suis trouvé confronté a été relative au budget des ateliers, lorsqu’ils furent instaurés de façon plus systématique, avec la mise en place du Club ; l’administratrice de cette époque refusait systématiquement de les aider financièrement et il a fallu que je me substitue a elle. À côté de cela, Oury se méfiait beaucoup de quelque chose qui existait dans la plupart des établissements publics, à savoir l’existence d’ergothérapeutes ou de sociothérapeutes spécialisés qui fonctionnaient de façon autonome par rapport au reste du personnel et qui devaient d’ailleurs acquérir ultérieurement une qualification particulière. Ça ne nous paraissait pas souhaitable, parce qu’au contraire on voulait à tout prix éviter que les activités ne deviennent stéréotypées, refermées sur elles-mêmes. Pour nous, le but n’était pas de parvenir à stabiliser une activité particulière. Son fonctionnement ne nous intéressait que pour autant qu’il permettait d’enrichir les rapports sociaux, de promouvoir un certain type de responsabilisation, aussi bien chez les pensionnaires que dans le personnel. Donc, nous n’étions pas trop favorables à l’implantation d’ateliers standardisés (vannerie, poterie, etc.) avec le ronron du responsable qui vient faire son petit boulot à longueur d’année et avec des pensionnaires qui viennent là régulièrement, mais de façon un peu mécanique. Notre objectif de thérapie institutionnelle n’était pas de produire des objets ni même de produire de « la relation » pour elle-même, mais de développer de nouvelles formes de subjectivité. Alors, à partir de là, toutes sortes de problèmes se posent sous un angle différent : on s’aperçoit que pour faire des ateliers, pour développer des activités, le plus important n’est pas la qualification du personnel soignant (diplôme d’infirmier, de psychologue, etc.), mais les compétences de gens qui peuvent avoir travaillé dans le domaine agricole ou comme lingère, cuisinier, etc. Or, bien entendu, pour pouvoir suffisamment dégager ces personnes de leur service, de leur fonction et pour pouvoir les affecter au travail des ateliers et des activités rattachées au Club, il est nécessaire d’inventer de nouvelles solutions organisationnelles, parce que sinon ça déséquilibrerait les services. En fait, ça n’allait de soi d’aucun point de vue, ni dans la tête du personnel soignant, ni dans celles des personnes directement concernées. Il a donc fallu instituer un système, qu’on pourrait dire de dérèglement de l’ordre « normal » des choses, le système dit de « la grille », qui consiste à confectionner un organigramme évolutif où chacun a sa place en fonction 1) de tâches régulières, 2) de tâches occasionnelles, 3) de « roulements », c’est-à-dire de de tâches collectives qu’on ne veut pas spécialiser sur une catégorie particulière de personnel (exemple : les roulements de nuit, les roulements qui consistent à venir à 5 h du matin, la vaisselle, etc.). La grille est donc un tableau à double entrée permettant de gérer collectivement les affectations individuelles par rapport aux tâches. C’est une sorte d’instrument de réglage du nécessaire dérèglement institutionnel, afin qu’il soit rendu possible, et, cela étant, pour qu’il soit « cadré » (...)

(...) La grille est alors un instrument indispensable pour instaurer un rapport analytique entre les différentes instances institutionnelles et les affects individuels et collectifs. Affects et affectations : la grille, c’est quelque chose qui est chargée d’articuler ces deux dimensions. Dans une perspective idéale ! Car dans les faits, c’est un problème complexe parce que, dès lors que vous renoncez à la rigidité des organigrammes technocratiques, vous vous heurtez à une multitude de difficultés ; les choses en apparence les plus simples se compliquent. Ce qu’on peut répondre aux technocrates, c’est qu’avec quelques notes de musique on peut aussi bien faire une musique très simple, par exemple une musique modale, qu’une musique infiniment riche. Il faut pour cela changer les gammes de référence, faire de la polyphonie… Avec une institution c’est pareil. On peut faire du plain-chant où chacun reste assujetti à une ligne monadique. On peut, au contraire, développer des compositions baroques d’une grande richesse. On s’est aperçu qu’avec une population de cent pensionnaires et quatre-vingt membres du personnel, on pourrait faire des choses d’une complexité incroyable. Pas pour le plaisir de la sophistication, mais parce que c’est nécessaire pour produire un autre type de subjectivité. On peut aussi concevoir des systèmes d’un type beaucoup plus monacal, où chacun trouve sa place au rythme des heures canoniales. Mais il faut admettre qu’il peut être nécessaire de composer des musiques institutionnelles polyphoniques et symphoniques si on veut essayer de saisir de façon plus fine les problèmes subjectifs inconscients relatifs au monde de la psychose.

Singulariser les trajectoires dans l'institution

Cela m’amène à une réflexion plus générale sur les finalités de la grille. Quelquefois on a pensé que ce système avait été instauré dans un souci d’autogestion, de démocratie, etc. En réalité, comme je le disais au début, l’objectif de la grille c’est de rendre articulable l’organisation du travail avec des dimensions subjectives qui ne pourraient l’être dans un système hiérarchique rigide. Complication donc, pas pour le plaisir, mais pour permettre que certaines choses viennent au jour, que certaines surfaces d’inscription existent. Par exemple, pour que certains membres du personnel puissent être présents dans des activités qui les intéressent alors qu’avec un organigramme fixe, cela ne leur serait pas possible. Ces modifications d’affectation dépendent alors de la capacité de la grille à devenir un système articulatoire.

Si vous souhaitez en lire plus, la version entière du texte est disponible ici.

Photo. Diane Arbus, Untitled.

Sa première rétrospective française est à voir jusqu'au 5 février au Jeu De Paume